What are the potential complications of this fracture?

Stiffness

This consequence of the treatment of a fracture of the tibia makes it clear that the process can sometimes take a long time. Not using the muscles and joints for an extended period can result in deterioration and an increased risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee or ankle. This was more common when long leg casts were used for extended periods. The injury itself does not damage the joints (although the muscles may certainly be injured) so early mobilization is effective in preventing this complication. In order to prevent this complication an exercise program as outlined in the Rehabilitation section is needed once the bone is healed strongly enough to withstand stress.

Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES)

This rare but serious condition can occur after about one in fifty tibial fractures. Fat globules from the bone marrow enter the blood circulation via damaged vessels and pass to the lungs and brain. Under certain conditions this sets up an inflammatory response compromising lung function and clouding consciousness. Often the first sign is confusion, followed by respiratory problems. The condition itself is short lived and self-limiting but the patient may need intensive care, including ventilator support, in the short term. Formerly, this rare condition was fatal in 10 percent of FES cases; with early recognition and aggressive supporting treatment this figure is now much less. However, it does remain one of the few complications of otherwise straightforward fractures that can provoke an emergency.

Infection

Open fractures are common tibial injuries and have an increased risk of infection because the bone comes through the skin and is contaminated at the scene of the accident. Surgical site infections can also occur when a fracture is operated on. This means that infections caused by bacteria are seen in a number of patients with tibial fractures (two to five percent). Most patients who have an open fracture or an operation receive antibiotics to reduce the chance of this complication. An infection is suspected when the wound remains red, tender, and swollen longer than normal. If it breaks open, if pus drains from the wound, or if bacteria are cultured from the wound, the diagnosis is confirmed.

High doses of antibiotics are given intravenously and in most cases the wound is opened to clean out dead and infected tissue and prevent pressure build up. In some situations, beads containing antibiotics are placed in the wound for a few days to achieve high local levels of the medication.

Fixation of the fracture is usually maintained until the fracture is healed. Then the implants may be removed because cracks or scratches on the surface may harbor bacteria.

The aim of treatment is to heal the infection and the fracture. Established bone infection may be very difficult to eliminate and may cause failure of healing. Most often the measures taken to treat the infection do result in healing the fracture and eliminating the infection. It is undeniable, however, that an infection results in a lot more trouble and usually some additional surgery.

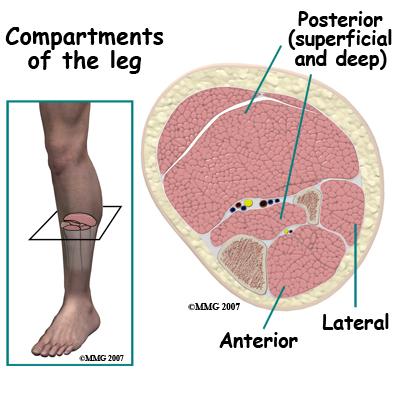

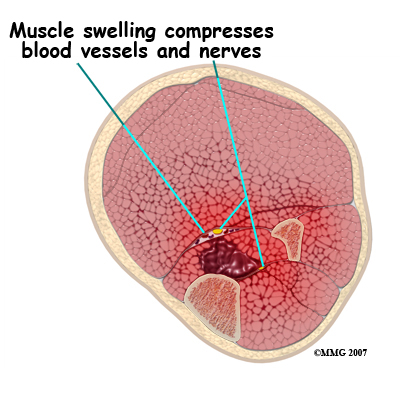

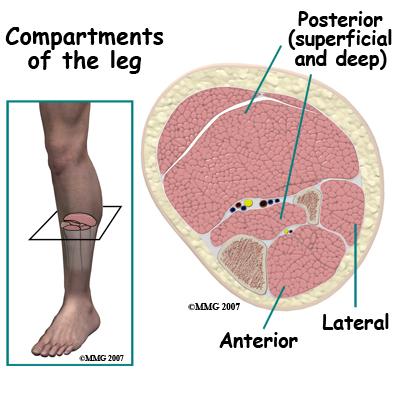

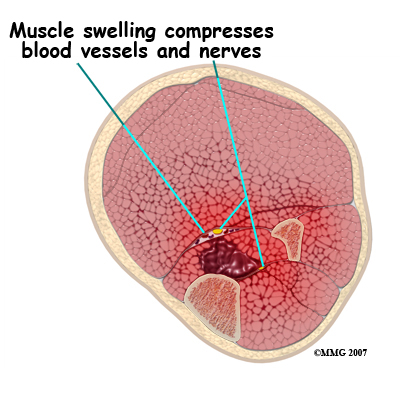

occurs when bleeding into the muscle compartments in the leg raises the intra-compartment pressure to levels that slow or stop blood flow in those compartments. Muscles in the leg (and arm, hand and foot) are contained inside compartments bounded by tough inelastic sheets of fibrous tissue. There are four compartments in the leg. The anterior compartment is the soft region in the front outer side of the leg - to the outer side of the shin bone. The lateral compartment is on the outer side and there are two posterior compartments in the calf at the back of the leg.

Even quite a small amount of bleeding into one or more of these compartments can cause a problem. This problem can be made worse if the leg is compressed from the outside by a cast or tight dressing. The fundamental problem is that the muscle tissue will die if there is insufficient blood supply. Dying muscle is very painful and unremitting pain is the most reliable sign of a compartment syndrome. However, all fractures are painful and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the pain that is normally present after a fracture and the pain of a compartment syndrome. In the latter case the pain is made worse by contracting or stretching the affected muscle; this is one of the reasons the doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists insist that patients move their toes, feet and ankles after a fracture.

If a compartment syndrome is diagnosed an emergency operation is needed to release the pressure. This is called a fasciotomy and may involve a big opening of the skin of the leg. Once the skin is opened the muscle compartments are also split open and the pressurized contents allowed to bulge out. This relieves the pressure and the blood supply to the muscle can resume. If this procedure is done before any muscle dies the long-term outlook is good, although the wound may require skin grafting and be unsightly. If some muscle death (necrosis) has occurred these parts may shorten up causing contractures and clawing of the toes as well as weakness of the affected muscle.

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome sometimes occurs months or years after the injury. When the patient returns to heavier activities or sports he/she finds that the leg rapidly becomes painful. The pain is made worse by moving the foot or pressure over the muscle and is slowly relieved by resting. This condition can be investigated by measuring the intra-compartment pressures before and after exercise. It is relieved by fasciotomy and the outcome after treatment is usually satisfactory.

Of all the long limb bones the tibia has the worst reputation for not healing. is a clinical diagnosis. It means that in the doctor's opinion, the bone will not heal without further intervention. Delayed union is the state where the bone is taking longer than normal to heal but there is sill a chance it will heal without surgery. Obviously there is an overlap between these two complications as all "nonunions" were "delayed unions" at an earlier point.

Of all the long limb bones the tibia has the worst reputation for not healing. is a clinical diagnosis. It means that in the doctor's opinion, the bone will not heal without further intervention. Delayed union is the state where the bone is taking longer than normal to heal but there is sill a chance it will heal without surgery. Obviously there is an overlap between these two complications as all "nonunions" were "delayed unions" at an earlier point.

Clinically, a non-united tibia is found to be painful and to hurt more on bearing weight or on stressing the leg. The pain does not get better with time as occurs with normal healing. Often one cannot feel any movement at the fracture site, but in florid cases one can. The x-ray shows a gap between the fracture fragments and in some cases the formation of a pseudo-joint. It may be necessary to get a CT scan of the region to make sure of the diagnosis. Getting a good image is often made difficult by the presence of metal implants used to treat the fracture.

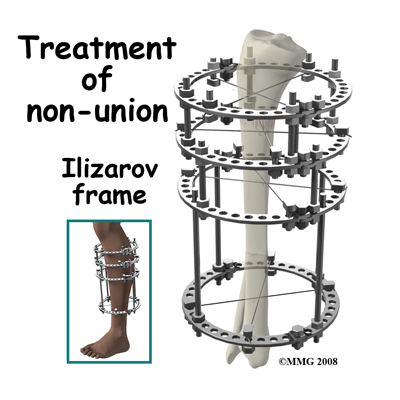

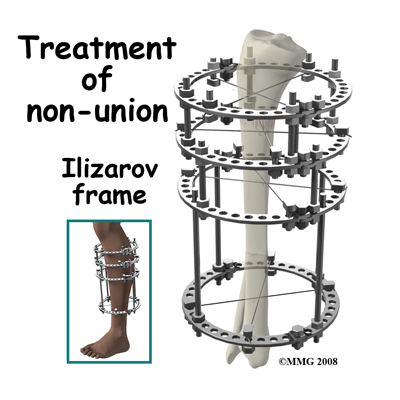

Treatment of a nonunion is individualized to each different case. Nonunion is more common if the original injury was treated nonoperatively. If surgery has not been undertaken before, the treatment will likely be rigid internal fixation and bone grafting. Bone grafting alone has been used and may be combined with removal of a small section of the fibula if it is thought that the healed fibula is holding the fracture fragments apart. If the fracture has already been operated on the fixation will most likely be replaced with some other system that imposes compression on the fracture site.

In really difficult cases, the Ilizarov technique may be used. The nonunited segment of bone is removed and freshened ends of normal bone are held together with an external frame. A second cut is made in the normal bone higher up the leg and the frame is used to lengthen the bone over time.

In most cases of nonunion surgery does achieve healing and the long- term outlook is good. Infected nonunion is a particularly difficult problem with a higher failure rate. The main adverse long-term outcome is loss of function caused by the prolonged treatment. If it takes years to heal the bone the muscles and joints of the leg are unlikely to recover fully.

Malunion

If the bone heals in a position that is shortened, angulated, or rotated it may be said to be mal-united. Often this is not a significant problem and does not interfere with long-term function. Studies of malunion have not shown a significant risk of later arthritis of the knee or ankle.

Sometimes the degree of shortening or rotation may not be acceptable. Treatment would then require surgical correction of the malalignment. Surgical correction of a malunion requires cutting the bone, restoring the alignment then fixing the tibia using either internal fixation with a plate, intramedullary rod or external fixation device. These methods are usually successful in correcting the problem and giving a good long-term outcome.

Summary

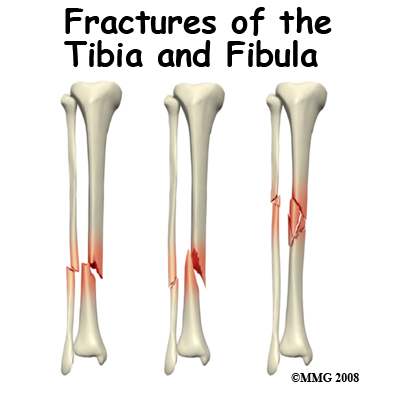

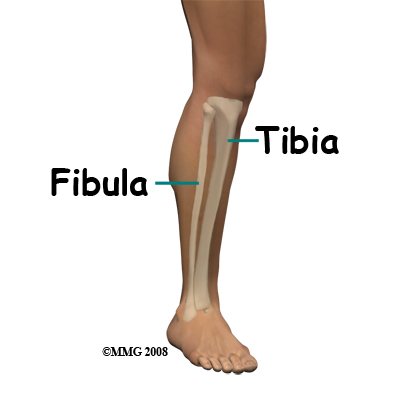

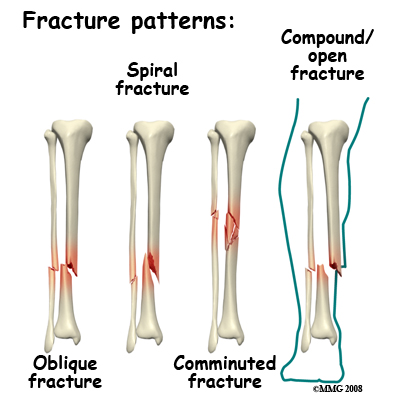

A fracture of the leg below the knee usually involves both bones of the shin, the tibia and the fibula. Fractures of the tibia are serious injuries which take many months to heal. There is a wide spectrum of injury from simple stable spiral fractures to severe open injuries with bone loss and massive damage to muscle, nerve and blood vessels. In most cases treatment is successful in its aims of saving the patient's life and limb, healing the fracture, and restoring function, but treatment can be prolonged and there are many complications to avoid.

Portions of this document copyright MMG, LLC.

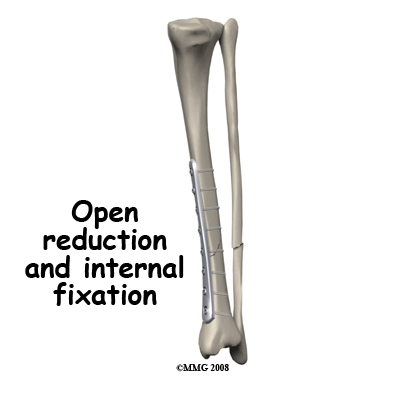

If the fracture has moved, it may be possible to correct the position by

If the fracture has moved, it may be possible to correct the position by  The operation involves exposing the fracture and moving the fragments back into the correct position. This position is then held by a metal plate secured above and below the fracture with screws. Plates are now available which match the shape of the tibia almost exactly. This allows a minimally invasive approach to plating the tibia where the plate is introduced under the skin.

The operation involves exposing the fracture and moving the fragments back into the correct position. This position is then held by a metal plate secured above and below the fracture with screws. Plates are now available which match the shape of the tibia almost exactly. This allows a minimally invasive approach to plating the tibia where the plate is introduced under the skin.

Of all the long limb bones the tibia has the worst reputation for not healing.

Of all the long limb bones the tibia has the worst reputation for not healing.

(403) 679-7179

(403) 679-7179  concierge@one-wellness.ca

concierge@one-wellness.ca