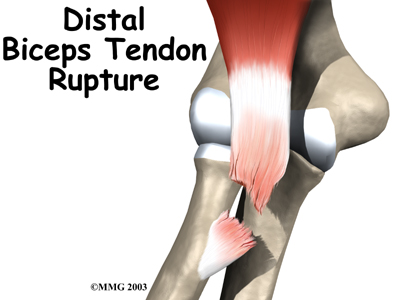

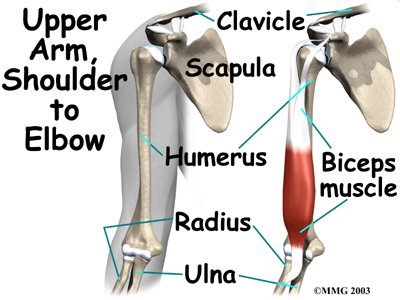

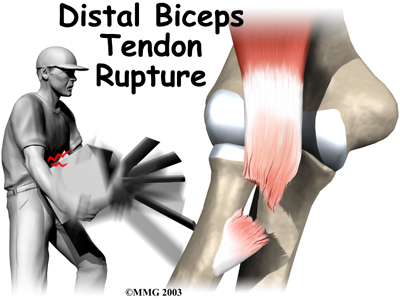

People who need normal arm strength get best results with surgery to reconnect the tendon right away. Surgery is needed to avoid tendon retraction. When the tendon has been completely ruptured, contraction of the biceps muscle pulls the tendon further up the arm. When the tendon recoils from its original attachment and remains there for a very long time, the surgery becomes harder, and the results of surgery are not as good.

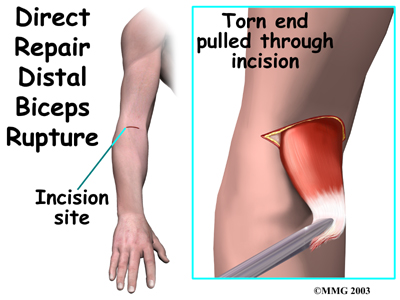

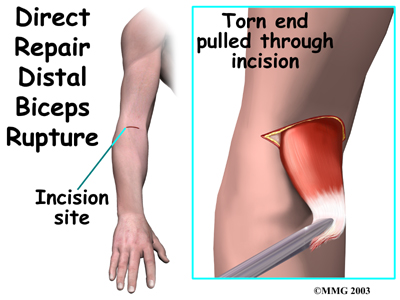

Direct Repair

Direct repair surgery is commonly done soon after the rupture. Doing a direct repair soon after the injury lessens the risk of tendon retraction.

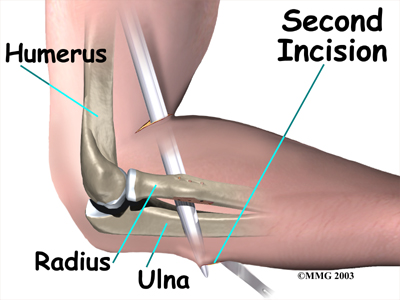

In a direct repair, the surgeon begins by making a small incision across the arm, just above the elbow. Forceps are inserted up into this incision to grasp the free end of the ruptured biceps tendon. The surgeon pulls on the forceps to slide the tendon through the incision.

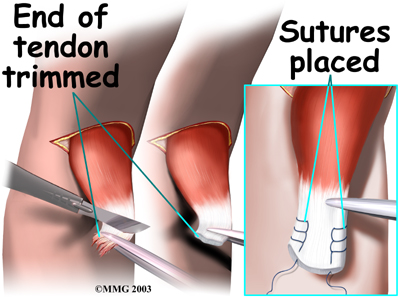

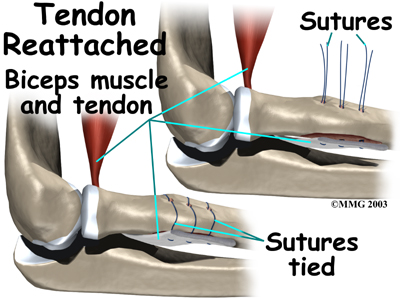

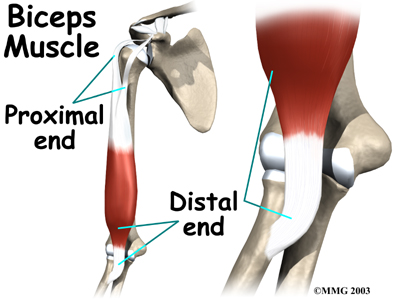

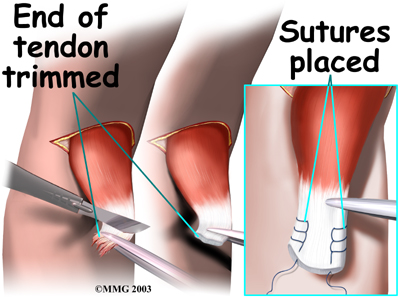

Attention is given to the . A scalpel is used to slice off the damaged and degenerated end. Sutures are then crisscrossed through the bottom inch of the distal biceps tendon.

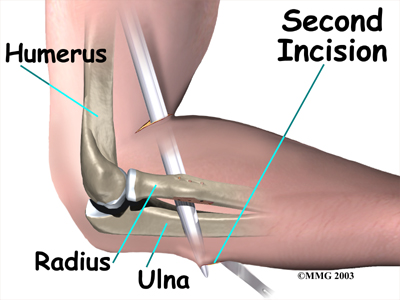

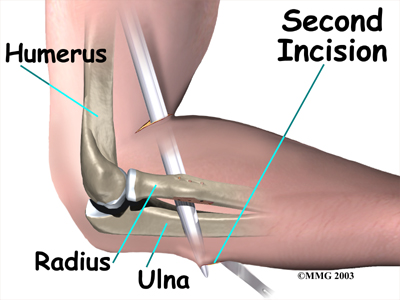

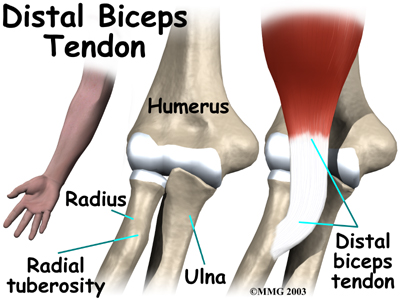

A curved instrument is passed through the incision and directly between the radius and ulna bones. The surgeon pushes the instrument through this space, puncturing the muscles and soft tissues. The surgeon feels the back side of the forearm for the spot where the instrument is protruding. A is made at this spot.

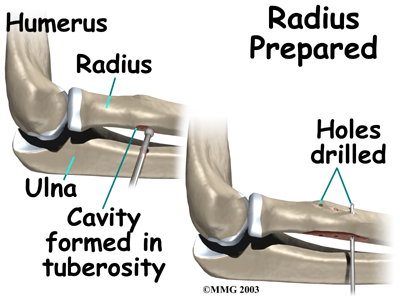

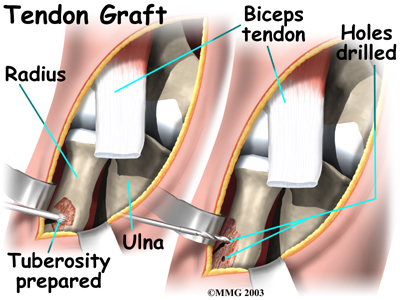

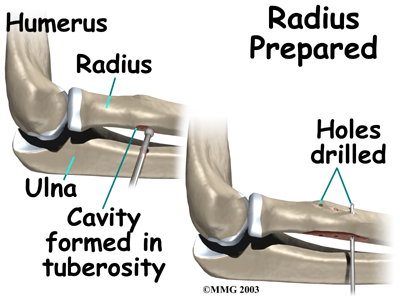

The original attachment on the radius, the radial tuberosity, is . An instrument called a burr shaves off the surface of the tuberosity. The burr is then used to create a small cavity in the bone for the tendon to fit inside. Three small holes are drilled into the top of the rim of bone to secure the sutures.

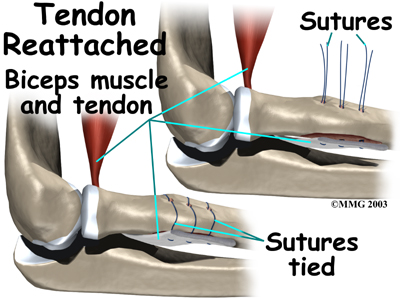

The tendon is passed between the radius and ulna, exiting through the second incision that was made on the back of the forearm. The sutures are threaded into the three holes that were drilled into the rim of the radial tuberosity. The surgeon ties the sutures, securing the . When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed either in a cast or a range-of-motion brace.

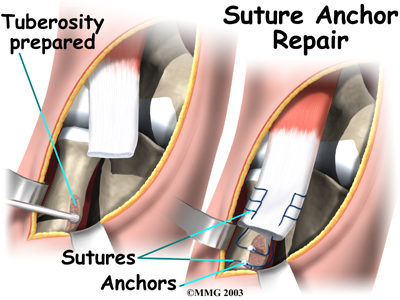

Suture Anchor Method

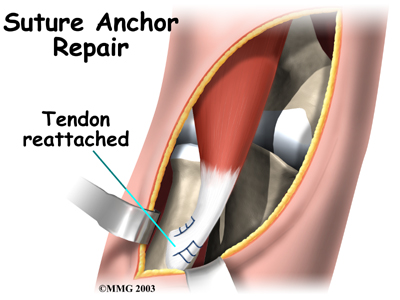

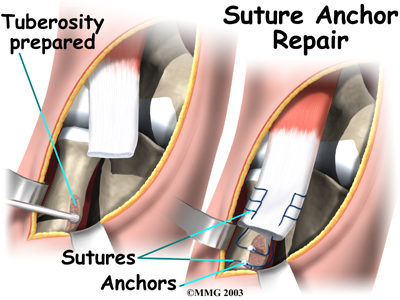

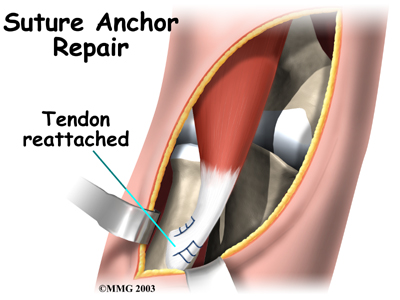

A new method of anchoring the torn tendon to the radius is gaining popularity. This method uses special anchors, called suture anchors, to fix the tendon in place. The procedure requires only one incision and appears to lessen the risk of myositis ossificans. Myositis ossificans is an abnormal healing response that causes bone to form in the muscles and soft tissues.

A new method of anchoring the torn tendon to the radius is gaining popularity. This method uses special anchors, called suture anchors, to fix the tendon in place. The procedure requires only one incision and appears to lessen the risk of myositis ossificans. Myositis ossificans is an abnormal healing response that causes bone to form in the muscles and soft tissues.

The surgeon begins by making a across the arm, just above the elbow. Along the outside edge of the arm, the incision curves and goes upward for a short distance. The skin and underlying tissues are pulled back using retractors. This reveals the front of the lower biceps muscle and allows the surgeon to avoid injuring nearby nerves and arteries. The fascia (connective covering over the muscle) is cut away so the surgeon can see the radial tuberosity.

The original attachment on the radius, the radial tuberosity, is by shaving off the surface with a burr. The burr is then used to create a small cavity in the bone for the tendon to fit inside. Two small suture anchors are embedded into the cavity in the radial tuberosity. These anchors can either be screwed into the bone or implanted like a staple. Each anchor has a long thread (suture) connected to it. The into the lower end of the tendon and crisscrossed upward. The surgeon slides the sutures back and forth, which coaxes the end of the tendon into the cavity. When the end of the tendon is positioned in the cavity, the surgeon tightens the sutures, fixing the tendon in place.

When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed either in a cast or a range-of-motion brace.

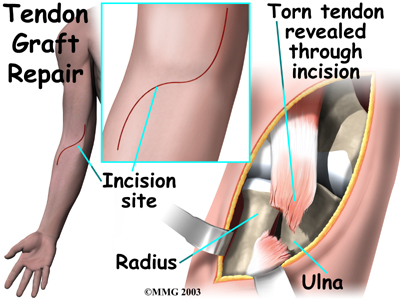

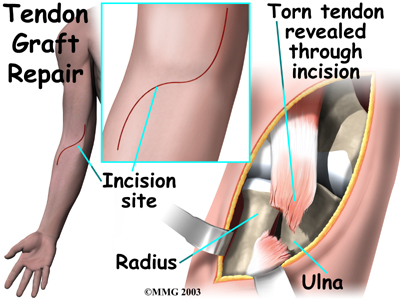

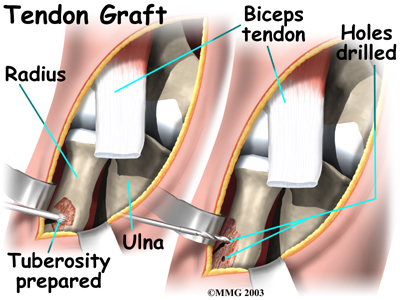

Graft Repair

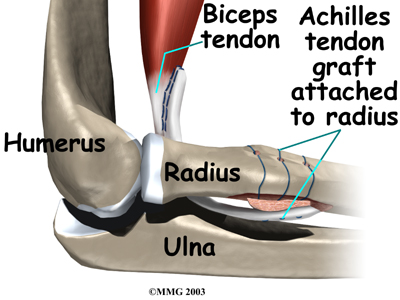

If more than three or four weeks have passed since the rupture, the surgeon will usually need to make a larger incision in the front of the elbow. Also, because the tendon will have retracted further up the arm, graft tissue will be needed in order to reconnect the biceps to its original point of attachment on the radial tuberosity.

The surgeon begins by making a across the arm, just above the elbow joint. The incision curves along the front surface of the upper arm to expose the lower part of the biceps muscle.

The surface of the is removed. A burr is used to create a small cavity within the tuberosity. Several suture holes are drilled around the rim of the tuberosity.

A curved instrument is passed through the incision and directly between the radius and ulna bones. The surgeon pushes the instrument through this space, puncturing the muscles and soft tissues. The surgeon feels the back of the forearm to find the point where the instrument is protruding. A is made at this spot.

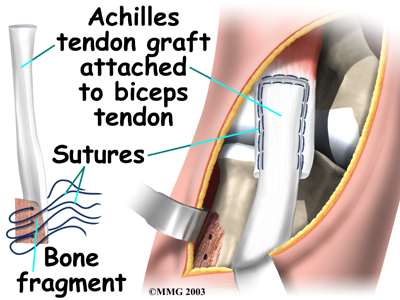

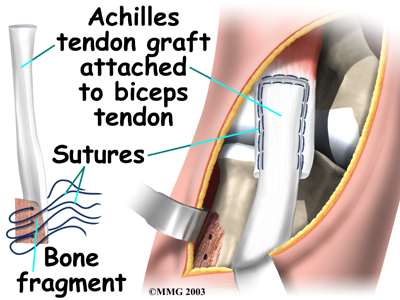

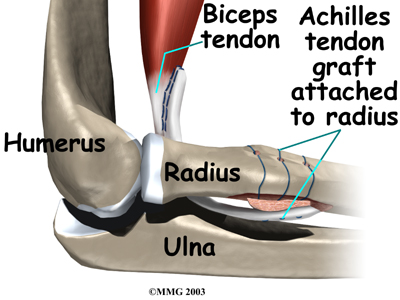

The surgeon then prepares a graft of tissue to lengthen the retracted biceps tendon. Some surgeons use a piece of hamstring tendon for the graft. Others use a section of the Achilles tendon where it attaches to the heel. This type of graft is usually an allograft, meaning that the tissue is taken from a cadaver (human tissue preserved for medical purposes).

When the is used, the surgeon leaves a small piece of the heel bone attached to the piece of tendon. Small holes are drilled into the piece of bone. Sutures are woven through these holes and will later be used to secure the end of the graft to the radial tuberosity. In this way, the graft will have a bone-to-bone connection that heals together. The healed bone solidly fixes the the graft to the radial tuberosity. After the graft is in place, its top end is then stitched over the front of the biceps muscle.

Next, the lower end of the graft is passed between the radius and ulna, exiting through the second incision that was made on the back of the forearm. The sutures from the bony end of the graft are threaded into holes that were drilled into the rim of the radial tuberosity earlier. The surgeon ties the sutures, to the radius.

When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed in a protective brace.

Portions of this document copyright MMG, LLC.

Why did I develop a rupture of the distal biceps?

Why did I develop a rupture of the distal biceps?

A new method of anchoring the torn tendon to the radius is gaining popularity. This method uses special anchors, called suture anchors, to fix the tendon in place. The procedure requires only one incision and appears to lessen the risk of myositis ossificans. Myositis ossificans is an abnormal healing response that causes bone to form in the muscles and soft tissues.

A new method of anchoring the torn tendon to the radius is gaining popularity. This method uses special anchors, called suture anchors, to fix the tendon in place. The procedure requires only one incision and appears to lessen the risk of myositis ossificans. Myositis ossificans is an abnormal healing response that causes bone to form in the muscles and soft tissues.

(403) 679-7179

(403) 679-7179  concierge@one-wellness.ca

concierge@one-wellness.ca